→ Informations : info@lefeuvreroze.com

FRANÇOIS MALINGRËY

WHERE ARE WE?

This question remains in tension in a world where the organisation of time and space responds to deeply mysterious codes. The inhabitants of the planet 'Malingrëy' never cease to question their own reason for existing. Yet they live in the absolute calm of a shared and accepted culture. Perhaps they have the answers to the questions we ask, but we are not able to hear them. The voices of the inhabitants of this planet remain silent.

Knowing where we are: naturalists, philosophers, geographers, cosmonauts and servants of all religions would be delighted to shed their light on such a subject. They have the arguments to illustrate their certainties about the state of the world. They willingly lend themselves to the exercise of a ritual capable of sacralising their vision by suggesting that they hold knowledge and reason.

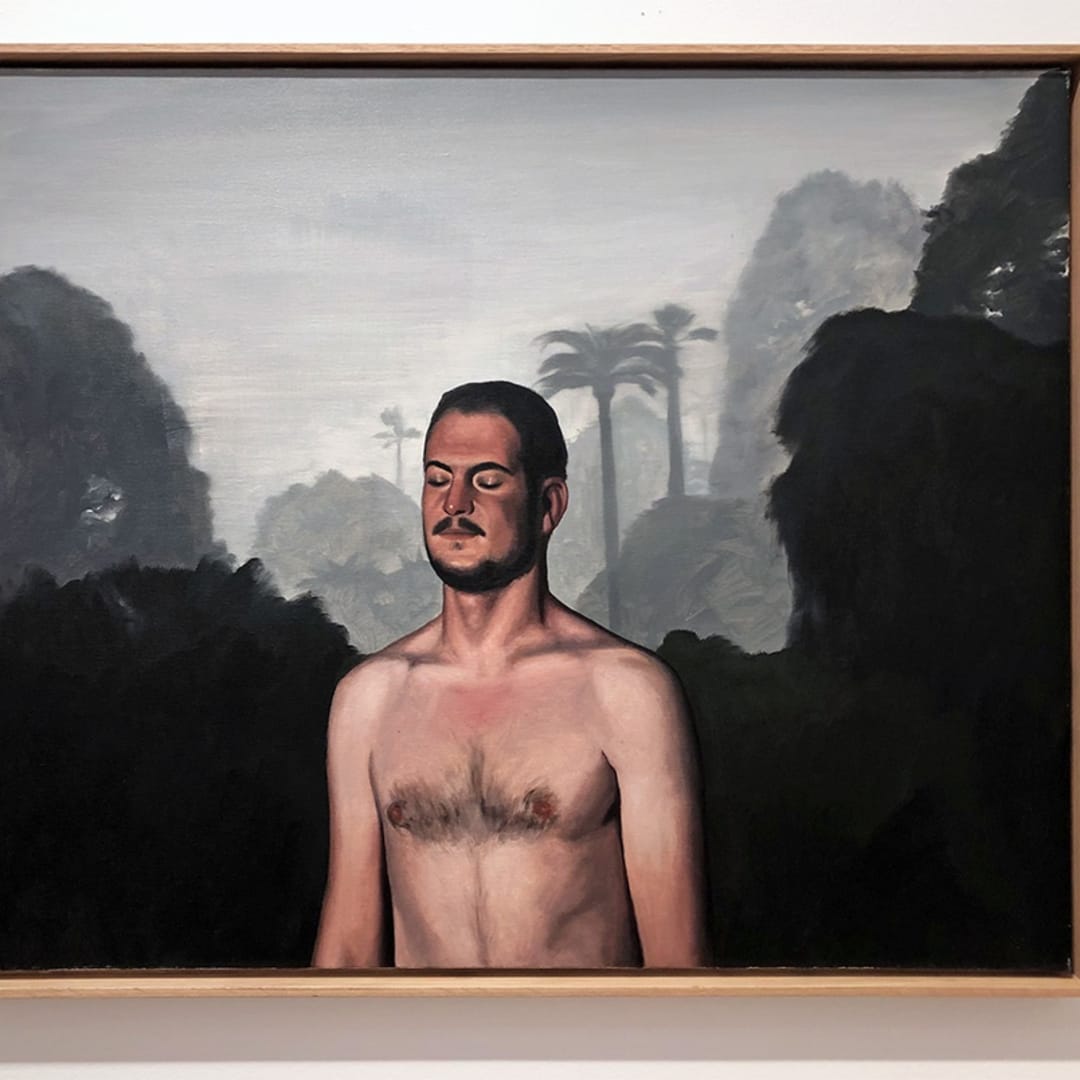

On the planet Malingrëy you have to take off your conventional clothes. Show yourself naked, or almost naked. To look at the birds without really being surprised by their presence and to simulate an act of agreement on an undefined theme. The fabrics, the sheets stretched in fluid materials organise the space to create both an unveiling and a mystery. Only aliens have the keys to read such a presence in the world. Yet it is to us, human earthlings, that the paintings are addressed. Where are we? How is it that we do not have the answer?

Should we direct our gaze differently?

Faced with the scenes offered by the artist, we never stop waiting. We immerse ourselves, we dive into a subconscious that reaches the soul and subjects it to the timeless universe of contemplation, both subversive and soothing: anything can happen. You come to realise that the accepted messages, those of the authorised decorum, are only a narrow way of seeing the world.

The inhabitants of the planet Malingrëy open doors to the abyss that saves us from certainties. We can doubt. At last. And end up understanding that it is enough to question to live.

Without waiting.

- Gilles Clément

Thalys Paris-Brussels on 30 January 2020

QUIET PEOPLE

In the context of French contemporary art, which has long been marked by a crisis in teaching and by the decline of painting as a mode of expression, François Malingrëy's appearance at the Salon de Montrouge in 2015 had everything to surprise. A recent graduate of the École des Arts Décoratifs in Strasbourg, the young artist seemed resolutely untouched by what might be termed "Duchampian academicism". At the end of the 20th century, the cult of the inventor of "Ready-made" and conceptual art had imposed a break with all forms of artistic tradition. Advocating self-affirmation and emancipation from models, art school teachers advised their students not to go to museums: creations had to appear without ancestors. But art education obviously failed to produce the sterile environment in which to experiment with this principle of spontaneous generation. Overwhelmed by the aspirations of a generation thirsty for images and by the facilities offered by the internet, the art of rupture suddenly gave way. For many young artists, Marcel Duchamp's subversive heritage is summed up in the impertinence of wanting to be on a par with the masters.

Precisely, François Malingrëy chooses a learned art. Under the pretext of depicting characters on the beach or interior scenes, he draws us into a fascinating maze of references, quotations and mise en abime. His paintings and sculptures draw on twenty centuries of art history, from the funerary portraits of the Fayum to the American realist school, via medieval funerary sculpture and Chinese pop art. From work to work, he invites us to follow a complex path, evoking a computer tree or a Borgesian labyrinth, but punctuated by recognisable signs like so many white pebbles.

Trained in the techniques of illustration, Malingrëy has a relaxed relationship with images. Like many artists of his generation, he does not hesitate to borrow them from heterogeneous repertoires, often delivered by computers, to recycle them in a new context. But this game of collage, which could turn out to be a bit vain, he practises as a visual artist, well convinced that a painting, "before being a warhorse, a naked woman or some anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colours in certain order assembled". While most of his contemporaries were content with virtual images, he seemed deeply attached to the materiality of the work. Valuing the work of the hand, he relies on the constraints of the craft, whether as a painter or a sculptor. It is with this in mind that he practices the art of portraiture, as others do their scales, with series closely framed on the model's face. Paradoxically, the almost artisanal practice of the chisel or the brush makes it possible to give substance to immaterial images. Doesn't the slowness of execution favour depth? At the age of thirty, the artist shows an exceptional mastery of plastic issues and if he resorts to borrowings it is in the service of a truly personal expression.

A literal quotation sometimes puts us on the trail. Pinned on the door, behind the model, a postcard reproduces one of the paintings by Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864-1916), a painter of silence if ever there was one. Does the Danish master live in the flat behind the door? The tone of the interior scenes painted by François Malingrëy depends on him, as does the setting of a banal intimacy in which The Woman and Children in Red Trousers is posed. But in this last painting, in a daring telescoping, itis a Pop Art icon that we recognise behind the chairs lined up along the wall. Tom Wesselmann's (1931-2004) blurred mouth disturbing its peaceful harmony.

François Malingrëy does not practice diversion through humour or parody. Far from the aggressive irreverence of a Yue Minjun (born in 1962), he pays homage. Most often, his references, as in a dream or in those waking moments when one has the intuition of a situation already experienced. So it is not necessary to identify the provenance of the model to be touched by a nostalgic grace. Erudition cannot be the only key to interpreting a complex work: are the figures grouped by the water still aware of Thomas Eakins' (1844-1916) Swimming hole? Elsewhere, the chromatic virtuosity of the young man sitting on the shore does not erase the memory of Hippolyte Flandrin's young bather.

In his treatment of the body, Malingrëy keeps an emotional distance. The nudity, mostly partial, is not seductive or enticing. The faces do not meet our eyes. This emotional distance is one of the components of the strangeness of the work. If Malingrëy refers to Flandrin, it is more to the hieratic monumentality of the church painter. Does he not have a particular sensitivity to religious painting, to which he owes certain procedures such as the golden backgrounds of his portraits. Sometimes his figures seem to be involved in a ritual that remains obscure. Does the group on the beach depict a descent from the cross? And will we ever know for what cult the Procession is intended? These paintings apparently follow the conventions of narrative. But the meaning resolutely eludes us. One thinks of Edward Hopper (1882-1967), another painter of silence who left his mark on the artists. We are also kept at a distance from this.

The repetition of motifs within the same work is one of the methods used to accentuate the dreamlike singularity: ibises reproduced like wallpaper motifs, characters from different angles - there is no question here of evoking twinnedness, but rather of introducing various stated of the model, of diluting its personality over the chole canvas. In the same way as the emotional distance or the separation from reality, the device allows us to concentrate our interest on the plastic issues.

Since his apperance at Montrouge, François Malingrëy's work has evolved towards a greater interiority. This trend is typical of great artists. From now on, the representation of a chair takes a meditative character. With their restricted chromaticism and measured format, Fire and Twilight are similar to the mystical density of certain German romantic landscapes.

Could the painter of the Quiet Ones also be a painter of the soul?

- Claude d'Anthenaise